Okasaki's PFDS, Chapter 6

This post contains my solutions to the exercises in chapter 6 of Okasaki’s “Purely Functional Data Structures”.

Exercise 6.1

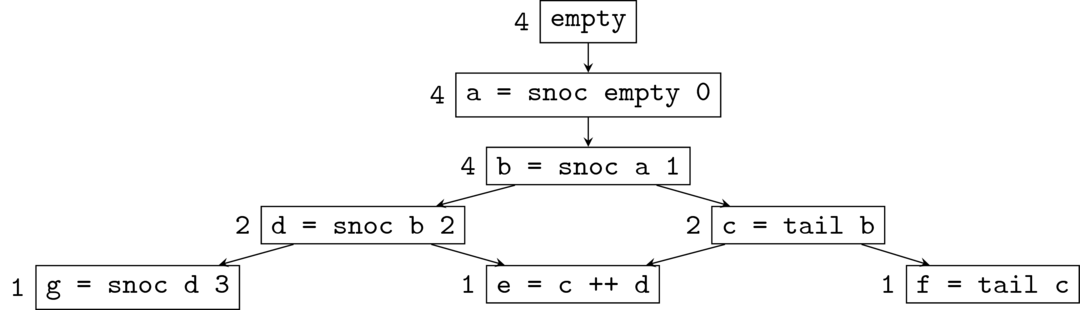

Draw the execution trace for the following set of operations.

a = snoc empty 0

b = snoc a 1

c = tail b

d = snoc b 2

e = c ++ d

f = tail c

g = snoc d 3Annotate each node in the trace with the number of logical futures at that node.

Solution 6.1

There are three terminal nodes (i.e. out-degree = 0): e, f, and g.

Each terminal node has precisely one logical future. The number of logical futures of a non-terminal node is the sum of the number of logical futures of its neighbours.

Exercise 6.2

Change the banker’s queue invariant to \(2\left| f \right| \ge \left| r \right|\).

- Show that the \(\mathcal O (1)\) amortised bounds still hold.

- Compare the relative performance of the two implementations on a sequence of one hundred

snocs followed by one hundredtails.

Solution 6.2

Item 1.

We assign the debt \(D(i) \le \min(3i, 2\left|f\right| - \left|r\right|)\) to the \(i\)th element of the front.

Every snoc that doesn’t cause a rotation increases \(|r|\) by 1 and decreases \(2\left|f\right| - \left|r\right|\) by 1. This violates the debt invariant by 1 whenever we just previously had \(D(i) = 2\left|f\right| - \left|r\right|\). We can restore the invariant by discharging the first debit in the queue, which decreases the rest by 1.

Every tail that doesn’t cause a rotation dereases \(\left| f \right|\) by 1, so decreases \(2\left|f\right| - \left|r\right|\) by 2. It also decreases the the index of the remaining nodes by 1, so decreases \(3i\) by 3. Discharging the first three debits in the queue restores the debt invariant.

Now for a snoc that causes a rotation. Just before the rotation, the invariant guarantees that all debits in the queue have been discharged, so after the rotation the only undischarged debits are those created by the rotation itself. Suppose \(\left| f \right|=m\) and \(\left| r \right|=2m+1\) at the time of the rotation. Then we create \(2m+1\) debits for the reverse and \(m\) for the append. The placement of debits is as in the book, which is summarised as follows.

\[ \begin{align} d (i) &= \begin{cases} 1 & i < m \\ 3m+1 & i = m \\ 0 & i > m \end{cases} \\ D (i) &= \begin{cases} i + 1 & i < m \\ 3m+1 & i \ge m \end{cases} \end{align} \]

The debit invariant is violated at \(i=0\) (since \(D(0) = 1 > 0\)) and at \(i = m\) (since \(D (m) = 3m + 1 > 3m\)). Discharging one debit from the zeroth node restores the invariant.

Finally, consider a tail which causes a rotation. There are two cases:

- Either \(\left| f \right| = m\) and \(\left| r \right| = 2m + 1\); or

- we have \(\left| f \right| = m\) and \(\left| r \right| = 2m + 2\).

The first case is analogous to that of snoc; discharging one debit will restore the invariant.

For the second case, we have one more debit than in the first case, which we place on the zeroth node. Now

\[ \begin{align} d (i) &= \begin{cases} 2 & i = 0 \\ 1 & 0 < i < m \\ m+1 & i = m \\ 0 & i > m \end{cases} \\ D (i) &= \begin{cases} i + 2 & i < m \\ 3m+2 & i \ge m \end{cases}. \end{align} \]

We can restore the invariant by discharging two debits from the zeroth node.

Item 2.

Since all suspensions are evaluated, the cost of 100 snocs followed by 100 tails is the complete cost of this sequence of operations. That is, we can pretend that all evaluation is strict.

The only possible difference is in the sum of the lengths of lists that need to be reversed. With the invariant \(\left| r \right| \le \left| f \right|\), this cost amounts to \(2^0 + 2^1 + \dots + 2^5 = 2^6 - 1 = 63\). With the invariant \(\left| r \right| \le 2\left| f \right|\), this cost amounts to \(3^0 + 3^1 + 3^2 + 3^3 = 40\). Thus, we would expect the second invariant to exhibit better performance for the execution trace above.

Exercise 6.3

Prove that findMin, deleteMin, and merge also run in logarithmic amortised time.

Solution 6.3

The proofs are essentially dual to those of Exercise 5.3.

findMin

Let h be a heap of size \(n\). Then findMin h makes a call to removeMinTree, which is linear in the length of the list. Since there are \(\log n\) elements in the list, the complete cost of findMin is logarithmic. We must also add the potential, but this is at most \(\log n\), so findMin has indeed \(\mathcal O (\log n)\) time.

merge

The unshared cost is constant. Let h1, h2 be binomial heaps of sizes \(n_1\), \(n_2\), respectively. The shared cost is bounded by \(\log n_1 + \log n_2 + k\), where link is called \(k\) times. Since \(\Phi (m+n) - \Phi (m) - \Phi (n) = -k\), we have \(\Psi (n_1+n_2) - \Psi (n_1) - \Psi (n_2) = k + d (n_1 +n_2) - d(n_1) - d(n_2)\), where \(d (x)\) is the number of bits of \(x\). Thus, the potential increase is greater than \(k - \log n_1 - \log n_2\), giving an amortised cost \(\mathcal O (\log n_1 + \log n_2)\).

deleteMin

Now we show that deleteMin is also logarithmic. We start with a heap h with \(n\) elements. The unshared cost is constant. The shared cost consists of: a call to removeMinTree, which is \(\mathcal O (\log n)\); reversing the list of children, which is \(\mathcal O (r)\); and a call to mrg, which is \(k + r + \log n\) where \(k\) is the number of calls to link. As with merge, the increase in potential is \(k - 2\log n\), leaving us with an amortised cost of \(\mathcal O(r + \log n)\).

Exercise 6.4

Show that removing the keyword lazy from the definitions of merge and deleteMin doesn’t change the amortised complexity of these funtions.

Solution 6.4

For merge, we saw that the complete cost is \(\log n_1 + \log n_2 + k\) and the potential increase is \(k - \log n_1 - \log n_2\). Thus, the amortised cost is \(\mathcal O (\log n_1 + \log n_2)\) whether merge is lazy or not. A similar argument also works for deleteMin.

Exercise 6.5

Implement a functor SizedHeap that transforms any implementation of heaps into one that explicitly maintains the size.

Solution 6.5

See source.

Exercise 6.6

Show that the following break the \(\mathcal O (1)\) amortised time bounds.

- Never force

funtilwbecomes empty. - During

tail, don’t changefbut instead just decreaselenfto indicate that the element has been removed.

Solution 6.6

Item 1

When analysing snoc or tail, part of the shared costs comes from the suspension $(f' @ rev r). If f' = force f, then evaluating this suspension is linear, as Okasaki shows. If f' = f, then evaluating this suspension is slower than linear. This is due to the fact that we have cascading dependencies of nested suspensions

For \(n = 2^k - 1\), the suspension would contribute to a shared cost of

\[ (2^{k-1} + 2^{k-1} - 1) + \dots + (2^0 + 2^0 - 1) = 2n - k - 2 \]

Since the increase in potential is \(n\), the amortised cost is \(\mathcal O (n)\), which isn’t constant.

Item 2

This change has two very obvious drawbacks:

it renders the algorithms incorrect.

For example,

head . tail . snoc 1 (empty)should yield an error but instead yields1.it is incredibly memory inefficient.

For example,

iterate (tail . snoc 1) empty !! kuses at least \(\mathcal O (k+1)\) memory instead of constant memory.

We need to show that it is also inefficient with respect to the time complexity. The \(\left| f \right|\) in the potential should be interpreted as lenf instead of length f in order to guarantee that the potential is zero when we force the suspended list. Calling snoc 1 on the queue iterate (tail . snoc 1) empty !! k will cause a rotation. However, the shared cost is now \(k + m + 1\) instead of \(2m+1\), where \(k \ge m\). For \(k = cm\), \(c > 1\), the new potential is \(2m+1\). Thus, the amortised complexity is \(1 + (k+m+1) - (2m+1) \ge (c-1)m\); that is, snoc is no longer constant time.

Exercise 6.7

Changing the representation from suspended list to a list of streams:

- Prove the bounds on

addandsortusing the banker’s method; and - Write a function to extract the \(k\) smallest elements from a sortable collection, proving that the funtion runs in \(\mathcal O (k \log n)\) time.

Solution 6.7

Item 1.

Due to the monolithic nature of the functions, it suffices to assign all debits to the root. This way, we could just maintain the debit invariant that the number of debits in the collection is \(D \le \Psi (n)\), where \(n\) is the length of the list. However, for the next part, we will require the list of streams representation and to assign the debits in an incremental fashion.

First, a couple of definitions. Let \(s_n (i)\) be the length of the ith stream in a collection of size \(n\). Then define \(\sigma_n (i) := \sum_{k=0}^i s_n (i)\). Note that \(n = \sigma_n (B-1)\) where \(B\) is the number of one-bits (streams) of \(n\).

Let \(d_n (i, j)\) be the number of debits on the jth element of the ith stream in a collection of size \(n\). Then

\[ D_n (i, j) := \sum_{l=0}^j d_n (i, l) + \sum_{k = 0}^{i-1} \sum_{l = 0}^{s_n (i)} d_n (k, l) \]

is the total number of debits up to the jth element of the ith stream in a collection of size \(n\). For convenience, we also define

\[ \Delta_n (i, j) := \sum_{k=0}^j d_n (i, k), \] the total number of debits up to the jth element counting only within the ith stream.

We maintain two debit invariants:

- each stream has \(\Delta_n (i, j) \le 2j\) debits; and

- the cummulative total of debits is \(D_n (i, j) \le \Psi (\sigma_n (i))\).

We show that the amortised cost of add is logarithmic in the size of the collection. Suppose we have a collection of \(n\) elements satisfying both debit invariants. Let \(k\) be the largest integer such that the first \(k\) bits of \(n\) are one-bits. The unshared cost of add is constant, as already shown in the book. The shared cost is \(2^{k+1}-2\), so we create that many debits. We assign two of these debits to each element of the new zeroth stream, except from the zeroth element. More precisely,

\[ \Delta_{n+1} (0, j) = 2j. \]

Since the size of the zeroth stream is \(s_{n+1} (0) = 2^k\), we have assigned a total of \(2(2^k - 1)\) debits as required. There are no more debits to reassign since

\[ D_n (k-1) \le \Psi (\sigma_n (k-1)) = \Psi (2^k - 1) = 0. \]

We have maintained the first invariant by construction but may have violated the second invariant. There are now a total of

\[ D_{n+1} (i, j) = D_n (i+k-1, j) + 2^{k+1} - 2 \] debits but are allowed at most \(\Psi (\sigma_{n+1} (i))\). Thus, we should pay off

\[ D_n (i+k-1, j) + 2^{k+1} - 2 - \Psi (\sigma_{n+1} (i)) \]

debits. This is at least \(\Psi (\sigma_n (i+k-1)) - \Psi (\sigma_{n+1} (i)) + 2^{k+1} - 2\). Note that \(\sigma_{n+1} (i) = \sigma_n (i+k-1) + 1\). It follows that we need to pay at least \(2B_i'-2\) debits from the first \(i\) streams, where \(B_i'\) is the number of one-bits of \((n+1) \mod 2 s_{n+1} (i)\); that is, the number of one-bits in the first \(i\) bits of \(n+1\). Therefore, we can restore the second invariant by paying off two debits from each stream. The realised shared cost is thus \(2B'-2\).

Showing that sort is linear is much easier. The second invariant guarantees that there are at most \(\Psi (n)\) debits. We can just pay them all off, giving basically the same analysis as with the physicist’s method.

Item 2.

See source.

Note that the first invariant allows us to access the head of each stream whenever we want. The unshared cost is \(2\log n\) since we make one pass over the streams to find the minimum and then one more pass to remove it. In order to be able to access the heads of all remaining streams, we should pay at most two more debits. Thus, extract 1 has complexity \(\mathcal O (\log n)\). It follows by induction, that extract k has complexity \(\mathcal O (k\log n)\).