Quadratic forms

When solving chapter 3 exercise 9 of BDA3, I felt like most of the algebra was unecessary. It turns out that it was indeed unnecessary, but I only realised how to simplify it after reading this StackExchange answer. The idea is that the sum of quadratic forms, Q1 and Q2, is again a quadratic form, Q. Since the exponents of the exponentials in both the prior and likelihood are quadratic forms, we can simply read of most of the equalities from the expression for the resulting quadratic form.

Theorem

Suppose we have two quadratic forms

Q1(μ)=A1(μ−a1)2Q2(μ)=A2(μ−a2)2.

Then Q(μ):=Q1(μ)+Q2(μ) is also a quadratic form, given by

Q(μ)=(A1+A2)(μ−a)+ca=A1a1+A2a2A1A2c=Q1(a)+Q2(a).

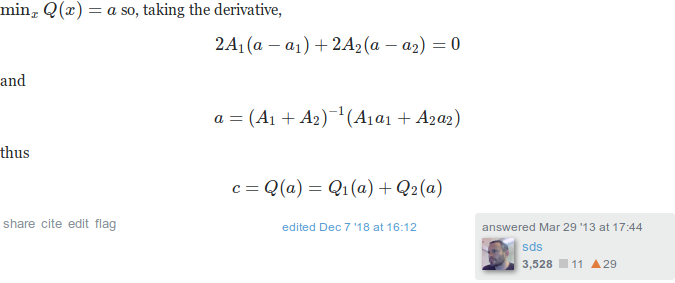

The proof is fairly straightforward, so I’ll just post a screenshot of the StackExchange answer:

Go give the guy an upvote.

BDA3 chapter 3 exercise 9

To see how the above theorem can help, let’s redo chapter 3 exercise 9 of BDA3. We have the two quadratic forms

Q1(μ)=κ0(μ−μ0)2Q2(μ)=n(μ−ˉy)2

from the prior and likelihood, respectively. Their sum is also a quadratic form Q:=Q1+Q2, which we can write as

Q(μ)=A(μ−a)+c

using the same notation as on StackExchange. Thus,

A=n+κ0a=1n+κ0(κ0μ0+nˉy)c=Q1(a)+Q2(a)

which already shows that

μn=κ0κ0+nμ0+nκ0+nˉyκn=κ0+n.

The identity νn=ν0+n is a simple calculation on the exponents of the σ factor. All that remains is to calculate c. Plugging in the numbers we get

c=κ0(κ0μ0+nˉyn+κ0−μ0)2+n(κ0μ0+nˉyn+κ0−ˉy)=κ0(nˉy−nμ0n+κ0)2+n(κ0μ0−κ0ˉyn+κ0)=κ0n2(ˉy−μ0n+κ0)2+κ20n(μ0−ˉyn+κ0)2=κ0n(μ0−ˉyn+κ0)2⋅(n+κ0)=κ0n(μ0−ˉy)2n+κ0.

Adding c to the remaining terms in the exponent of the exponential, gives us that

νnσ2n=ν0σ20+(n−1)s2+κ0nκ0+n(ˉy−μ0)2.

In summary, this simple theorem described above is enough to turn a page of nasty algebra into a few simple lines.